The Next Copernican rEvolution - Chapter 9 - A Brief History of Homo Sapien Fiction

“Yet the truly unique feature of our language is not its ability to transmit information about men and lions. Rather, it’s the ability to transmit information about things that do not exist at all. As far as we know, only Sapiens can talk about entire kinds of entities that they have never seen, touched or smelled. Legends, myths, gods and religions appeared for the first time with the Cognitive Revolution (30–70,000 years ago). Many animals and human species could previously say, ‘Careful! A lion!’ Thanks to the Cognitive Revolution, Homo sapiens acquired the ability to say, ‘The lion is the guardian spirit of our tribe.’ This ability to speak about fictions is the most unique feature of Sapiens language.” ~ Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

Once again let’s take a look at an example of how changes to the external physical reality affect our evolution on the inside, and then vice versa. We have explored genetic evolution and technical evolution and the evolution of our institutions, evolution of our economic systems, evolution of our energy systems…all seemingly external physical aspects of reality. But are they really reality? We will come back to answer this question, but first, let’s look at the history of human fiction. Israeli historian and professor Yuval Noah Harari has written a mind-blowing book entitled Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind1, in which he explores how humans have been able to dominate the world because of our unique ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers. And the reason we are able to do this, he argues, is due to one of our other unique abilities…the ability to believe in things that don’t actually exist. In other words, our ability to create and believe in fiction.

Harare describes this phase-change evolutionary development, “The period from about 70,000 years ago to about 30,000 years ago witnessed the invention of boats, oil lamps, bows and arrows and needles (essential for sewing warm clothing). The first objects that can reliably be called art date from this era as does the first clear evidence for religion, commerce and social stratification. Most researchers believe that these unprecedented accomplishments were the product of a revolution in Sapiens’ cognitive abilities…The appearance of new ways of thinking and communicating constitutes the Cognitive Revolution. What caused it? We’re not sure. The most commonly believed theory argues that accidental genetic mutations [external physical] changed the inner wiring of the brains [external physical] of Sapiens, enabling them to think in unprecedented ways and to communicate using an altogether new type of language [internal].”

So then, armed with this new tool, language, we proceeded to create fiction that had massive impact on the trajectory of mankind. We’ve seen in previous chapters how our external collective structures have grown larger and larger (tribal villages to city-states to nation-states to multi-national corporations) and our worldviews grew as well (egocentric to ethnocentric to world centric), so is it any surprise that our fictions would also grow larger and larger, to include more and more people across larger and larger areas. Indeed, Harari makes the case that it is our larger and larger fictions that have enabled humans to organize into larger and larger groups. Prehistoric tribal humans were naturally and easily able to organize into small bands, but to expand much further than that, language was needed, gossip was needed, stories were needed, myths were needed…in short, fiction was needed in order to get cooperation from larger and larger groups.

Harare describes the dynamics of this evolutionary force that would change humanity forever, “How did Homo sapiens manage to cross this critical threshold, eventually founding cities comprising tens of thousands of inhabitants and empires ruling hundreds of millions? The secret was probably the appearance of fiction. Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths. Any large-scale human cooperation — whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city or an archaic tribe — is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination. Churches are rooted in common religious myths. Two Catholics who have never met can nevertheless go together on crusade or pool funds to build a hospital because they both believe that God was incarnated in human flesh and allowed Himself to be crucified to redeem our sins. States are rooted in common national myths. Two Serbs who have never met might risk their lives to save one another because both believe in the existence of the Serbian nation, the Serbian homeland and the Serbian flag. Judicial systems are rooted in common legal myths. Two lawyers who have never met can nevertheless combine efforts to defend a complete stranger because they both believe in the existence of laws, justice, human rights — and the money paid out in fees. Yet none of these things exists outside the stories that people invent and tell one another. There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws, and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings.”

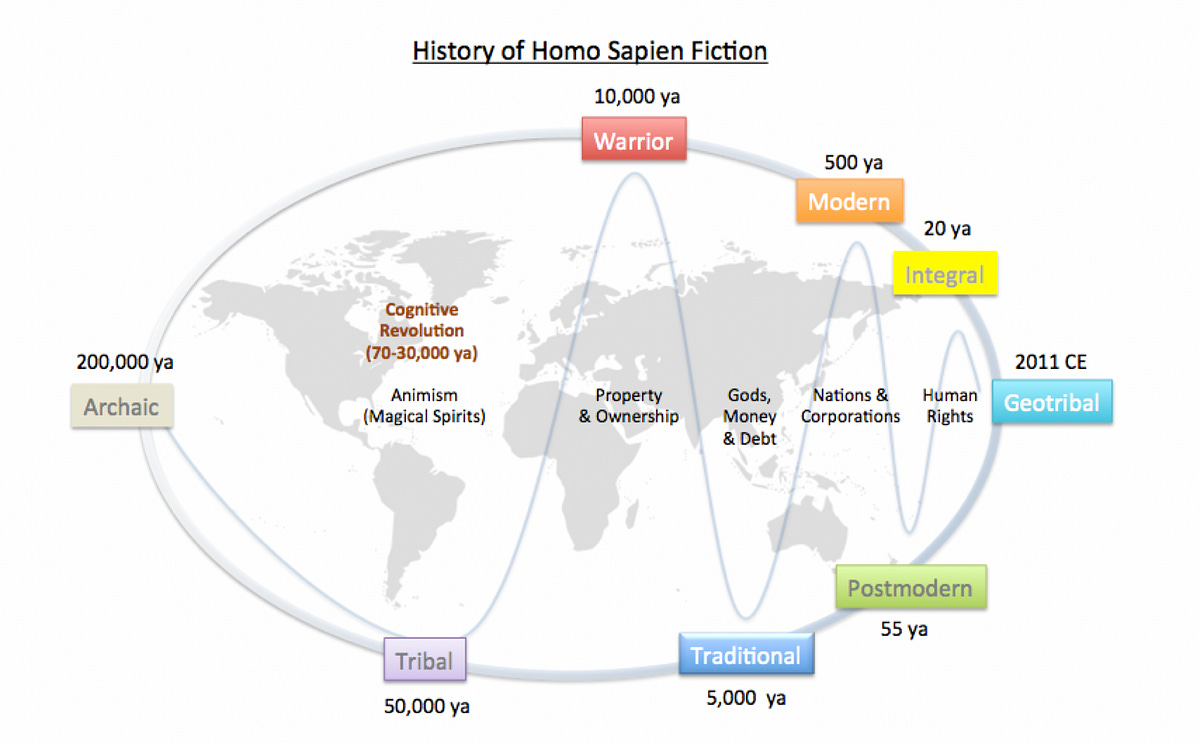

While the above statement may seem pretty hard hitting to those with any of the alluded to belief structures, I think Harari is not necessarily criticizing people’s beliefs, as much as he is merely stating how beliefs have been instrumental in our growth as a global species. In the diagram I’ve created above, you’ll see that the changes in our myths and fictions can pretty easily be correlated with, and overlaid on top of, the diagram of the different worldview eras, as well as our eras of external phase-changes with our systems and technologies, as described in the three previous chapters. These human myths and fictions also correlate with the development of our empathy. So in the tribal era, the protection of and appeal to magical spirits often extended no further than to the members of their own tribe. Then, with the advent of agriculture and early civilizations about 10,000 years ago some humans began creating invisible boundaries on the land and called it “property” and began issuing claims of “ownership”. But this was a new way of seeing the world that some indigenous peoples couldn’t understand (and still don’t), the notion that land and the earth could belong to anyone besides the “great spirits”. Then about 5,000 years ago notions of money and debt emerged, which coincided with the emergence of organized religion. We’ve already explored in chapter 4 how the notions of debt, sin, obligation and exchange got tangled up into ideas of morality and religious thought. We created a fictional thing called money, whether in the form of cowry shells or coins to symbolize and stand in place of real things that had real inherent value. In the modern era about 500 years ago, the emergence of fictional corporations emerged, like the East India Company2, for example. And then larger and larger units of human civilization emerged with the formation of nation states. Nation states — Spain, Portugal, etc. — worked with the early corporations to form major empires that spread throughout the world with colonialism. Then only about a hundred and fifty years ago did the fiction emerge that humans (or creatures) have inherent rights. When I say, or Harari says, that rights are fictional, it’s only in the sense that there are no laws of nature directly related to any so-called “rights”. In other words, if an animal or human, or black gay man, or aboriginal female falls off a cliff, that sentient being is going to smash into the ground below no matter how good or deserving that person or animal is. No matter what color that person’s skin is, her sexual persuasion, or his religious piety, mother nature and the laws of physics don’t care. As real as the concept of goodness is, or ought to be, it is nonetheless a human creation.

Now we are entering a new era that calls forward new fictions, new myths, new stories, if we are to survive and thrive in the near future. Perhaps as we challenge and reconsider the current fictions, we will actually create new stories that are closer to reality, or maybe we are beginning to move beyond stories altogether. As the Austrian contemporary spiritual teacher, Thomas Hübl said, “Humanity does not need a new story. We need to move beyond stories, to where reality actually unfolds. People who are awake are not looking for more stories. They are looking for less stories, in order to see life”.3

As I’ve indicated already I think everything that’s ever happened throughout our history, seemingly good or bad, has been a necessary part of our development, of our species growing up. However, even if we take a relativistic position by saying “everything was and is just as it should be”, that doesn’t mean that certain beliefs or myths are sustainable and non- detrimental to our survival as a species.

Harari describes this paradox and the conundrum it has gotten us into, “Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have thus been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations. As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google.”

Thus is the predicament we find ourselves in…fictional entities are determining (so far) our fate, our survival. At the risk of stating the obvious, or repeating myself, all major life systems are in decline. So clearly our current myths, be they religious or economic or political, are not sustainable. The good news is that these myths are not set in stone — they are changeable. Harari describes the impermanence of these seemingly unchangeable human myths, “The ability to create an imagined reality out of words enabled large numbers of strangers to cooperate effectively. But it also did something more. Since large-scale human cooperation is based on myths, the way people cooperate can be altered by changing the myths — by telling different stories. Under the right circumstances, myths can change rapidly. In 1789 the French population switched almost overnight from believing in the myth of the divine right of kings to believing in the myth of the sovereignty of the people. Consequently, ever since the Cognitive Revolution Homo sapiens has been able to revise its behaviour rapidly in accordance with changing needs. This opened a fast lane of cultural evolution, bypassing the traffic jams of genetic evolution. Speeding down this fast lane, Homo sapiens soon far outstripped all other human and animal species in its ability to cooperate.”

Global cooperation or global fragility…that is the collective paradox we are in. For the first time in human history we are able to cooperate globally, which is a good thing, right? Indeed it is, as long as our current global myths — our collective global story — is sustainable. But alas, it is not. Our current global story is about capitalism and money, not about human or environmental welfare. Our myths are that we are inherently greedy and competitive, rather than compassionate and innately good. Our economic system is about individualism and survival-of-the-fittest, rather than the good of the whole. Our entire ethos is about infinite consumption of “more and more”, rather than a steady state mentality of “enough”. Our entire way of life is based upon a scarcity story, rather than one of abundance, which we’ve already seen how it skews and corrupts our true human beingness. However, if it is true that we can change the global myths, then we are capable of cooperating globally, which could ensure not only the survival of our species, but indeed our thriving. But instead all that we have really done is increase our fragility to a global scale now. The operating system of our entire planet is now predicated on capitalism and money, which are entirely flawed myths. Therefore, our entire global economic system is susceptible to collapse, as the 2008 economic crisis hinted at. So if everything is connected (as it truly is) in ways that are good and life-affirming, well that’s a good and healthy thing. But if instead everything is connected through an underlying operating system that is not life- affirming or is actually destructive, the entire edifice of humanity is fragile, is subject to shocks and collapse.

In opposition to the fundamental principles of nature and evolution, we seem to be trying to do away with our species’ diversity and variety and replace it with a single monoculture called global capitalism. Mother nature and evolution favor diversity and variety, and yes, even disorder. As the Lebanese- American essayist and risk analyst Nassim Nicholas Taleb wrote, “Nature builds things that are antifragile. In the case of evolution, nature uses disorder to grow stronger.4”Look at the natural flourishing of fauna and flora throughout the world, many species of which we have yet to discover. Then look at capitalism and monetary economics, and see what it has encouraged. It is indeed a form of order on a massive scale, but could it be considered a positive form of order? Has the so-called free market created diversity or homogenization? Does not every town in America seem like every other town in America (and increasingly across the world), with its McDonalds and its Chili’s and its Walmart and its Walgreens on every corner, and so on and so on? And does our free market system create more small businesses and jobs, or does it tend toward monopoly, with fewer and fewer multi- national corporations accumulating more and more wealth and capital through the elimination of jobs in favor of robotics and automation? So right now we have so-called “order” not only on a global scale via corporations, but also through state governments. And this involves massive collusion between governments and corporations, to the extent that they are almost one and the same. This is not some sort of “new world order” conspiracy theory, it’s simply what our monetary system encourages.

But in reality, is any of this stuff really real? Are nation state boundaries real? Are corporate charters real? Are the gods and religions that don’t recognize the oneness in everything real? Is the imaginary money and debt that supposedly makes the world go around really necessary at all? Are the myths and stories we’ve been telling ourselves for millennia really immutable, are they unchangeable?

If, from a relativistic perspective, we see that there is a certain realness to everything we’ve been discussing, which indeed there is, then we can also make the connection that some stories are more life-affirming than others. Therefore, we should pay attention to, and change, the stories that affect the survivability of our species, as well as all sentient life on our planet. So let’s change our stories and systems to align with and support our rivers, trees and lions instead of our imagined entities like the United States and Google.

Now, if we agree that we need to create new stories of reality, then we must discuss one of the most important myths of our time that is so big that in addressing it we will inevitably be ushering in the next Copernican rEvolution. We will discuss the fiction of global debt.

» Next Chapter - Chapter 10: Q&A: Climate Change, Debt Fiction, and the JPEG Implosion — This Really, Really Changes Everything — A Discussion with a Banker

Chapter Index

Footnotes:

Yuval Noah Harari (born 24 February 1976) is an Israeli historian and the author of the international bestseller Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. He is a Professor at the Department of History of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The Corporation that Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern World, Nick Robins - http://www.amazon.com/The-Corporation-that-Changed-World/dp/0745325238

Thomas Hübl - What is humanity's new story? -

Nassim Nicholas Taleb - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antifragile